Apple Vision Pro Wants to be Two Products

A case study of how being opinionated on the use case of a product can help you grapple with the limitations of an improving technology in a v1 product

I remember when the iPhone came out. Same with the iPod (though I was much younger). At the time, Steve Jobs was one of my heroes. Apple developed products that were breakthroughs in their categories even though they weren’t ever the first. That approach gave Apple its current reputation for innovation and design.

The Vision Pro is really exciting. I can’t wait to get one. Palmer Luckey, founder of Oculus, presciently said that before something like this “can be something everyone can afford it has to be something people want.” Mission accomplished.

But it’s also overengineered. Mark Gurman say that Apple’s launch strategy is taking a “scattershot” approach and letting the market decide what it’s for. App developers aren’t tackling it yet, and the Vision Pro will launch with a smaller App Store than the iPhone or Apple Watch.

You see this problem throughout the products space. Designers are afraid to commit to certain use cases, lest they be wrong. Business planners fear not being able to cover a vertical. So no one has an opinion and every product can do everything, but only somewhat.

The great virtue of the Apple of old was focus and its predicate: choice. To make product choices, you must have a vision of what the product must be. That allows you to take advantage of nascent and amazing yet immature technologies to appear on the cutting edge.

The Vision Pro is an example of abandoning that approach. It wants to be two different products. Let’s explore.

iChoose

Apple went through two distinct periods, technologically, in its history: a Wozniak and a Jobs period. In the beginning, Apple developed myriad technological breakthroughs itself, many from the genius mind of Wozniak. The Apple I and Apple II were products of revolutionary engineering. The Mac took half a decade of hard invention, from the hardware to the GUI. This approach continued into John Scully’s tenure. Products like the Apple Newton and LISA, although commercially failures, involved home-grown technical wizardry on the hardware side. Apple even used to have its own factories in Cupertino.

The Jobs era was extremely different: the modus operandi was using existing, cutting edge technology that was on a steep growth curve and using design and use-case opinions to exploit it while working around the limitations of the technology at the time. Although the post-NeXT Apple had numerous technical innovations, none of the major breakthroughs came from Apple itself. Like a magician, this allowed Apple to redirect the attention of users away from the shortcomings of a technology while appearing cutting-edge by taking new tech that was obscure and bringing it to the mainstream for the first time, often used in a novel way. They took products where free wasn’t cheap enough but with technology that was on the bleeding edge to creatively design products the masses clamored for.

Let’s take two examples.

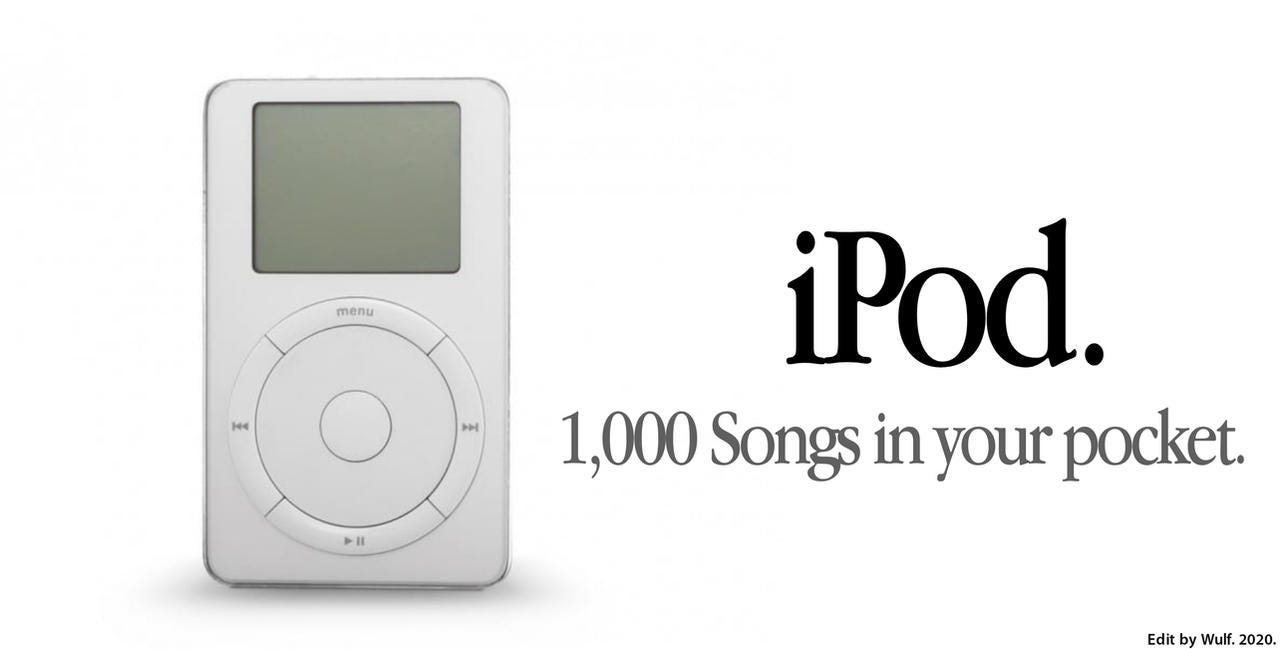

The original iPod ad, “1000 songs in your pocket,” highlighted its two big selling points: a large music library that was small enough to carry. Before the iPod, you got (at most) one of these. Apple’s major idea was that hard drives were getting much, much smaller, so you could fit 1000 songs on a single device. But Apple didn’t invent a better hard drive; it bought the smallest one it could find from Toshiba. The engineering efforts to make the technology work around the hard drive were immense. But because the use case was incredibly clear, everything else was able to be sacrificed. You couldn’t play videos because the processor was very underpowered and the 160-by-128 pixel screen was bare-bones. After all, the only thing the original iPod did was play music; it was practically an accessory to a Mac. Such simple functions required a new interface, which was found in the iconic scroll wheel (which was made externally, of course, by Synaptics). And because the iPod played music so well, no one even asked whether it could do anything else. Besides, time was on Apple’s side. With Moore’s Law, it wasn’t long until you had an iPod with a vibrant color screen that could even play video games.

The iPhone has a similar story. Apple didn’t even invent the pinch to zoom interface; it came out of Bell Labs. The actual tech was from a company called FingerWorks and the screen was manufactured by Corning. Apple’s main contribution was the software. It was basically a giant screen with big battery and a similarly big price. The battery, which had 1400 mAh, was nearly 25% larger than the 1150 mah that was standard. Despite that, the processor (which was made by Samsung; the P.A. Semiconductor acquisition was in 2010) still had to be underclocked by 33% to support acceptable battery life. The first iPhone didn’t ship with 3G and wouldn’t let you change your wallpaper! With these limitations, Apple couldn’t take the risk of allowing unlimited customizability. (You probably couldn’t do much as a developer, anyways.) Before “there’s an app for that,” there were only a few apps made by Apple. But they had a clear view of what the most compelling use cases would be—maps, texting, the web, video. So they wrote all of the first software. And because it was so good, no one even noticed.

What is key to both of these stories is that Jobs had already decided what the products would be used for in their first iterations and had a design that would make them magical. The limitations allowed him to act like a magician: he could point them in the direction of the amazing new technology while redirecting their attention from the limitations of technology as it stood at the time because it simply couldn’t do, or didn’t need, what it didn’t have. Then, as the technology steadily improved, he added in what was missing to end up with the products we know today.

This also helps visionaries explain their technology. When the iPad first came out, many commentators weren’t sure what it was for. But Jobs had a very clear view: it was the “in between” device. What did that mean? Leisurely reading and streaming. He literally put a living room chair on stage and sat on it, using that setting to demo made-for-iPad apps like iBook and the New York Times. If Jobs had thrown tablets at customers and said “you figure out what this is for!” it would have been difficult to grok. Being opinionated early on made the iPad easier to market, even though its uses have expanded over time. It’s the complete opposite approach to what Apple did with the Apple Watch even though both products were amorphous to consumers at the beginning.

Defining your use cases meticulously also allows you to have favorable price positioning, even when you are selling a premium product, because you get to define your competitors. When Jobs introduced the iPhone, he gave a masterclass in positioning. He immediately defined the phones that were his competition—conspicuously, the most expensive phones made by each of his competitors. Then he defined the iPhone as three products in one—not a product, a bundle of products. So $700 for a phone? Very expensive. But compared to the most expensive Blackberry, and an iPod, and a mobile browser, which would normally require a Mac? That made the iPhone’s premium prices seem like a good value: you were paying a lot, but you were getting even more. If Jobs had just introduced the phone without defining the use case, consumers and journalists would be comparing the iPhone to flip phones without even understanding the difference.

Lacking Vision

That brings us to Apple Vision Pro.

Apple’s new Vision Pro looks amazing. But it clearly came out of a different process than the iPod and iPhone. It didn’t take 1-2 years to create; it took nearly a decade. It’s overengineered. And yet Apple still hasn’t defined what it’s supposed to be for. It’s trying to straddle all levels of the spatial computing experience instead of picking specific use cases and building for them.

You hear a lot of reviewers say that “these aren’t really the devices we want” so all headsets are beta products. But what if it was possible to have those devices today by being smart about the product?

What I propose is that we can have it all, just not at once. Apple, like everyone else, is trying to cram two products into one and having to embrace too many trade-offs as a result. Instead, it should release two products. I call them Air Vision and Mac Vision.

Air Vision: The HUD

Think about pop culture representations of smart glasses. Minority Report, Free Guy, Her. They don’t look like Magic Leap, where you have complex graphics overlayed on the real world for games. They look like an avionics HUD. They provide subtle changes to the real world in a way that looks like a video game. The HUDs of our dreams help us get around the world with labels.

If you don’t need complex graphics, the technology is actually already out there to display simple information in regular-looking glasses, like the Intel Vaunt from 2018 and the XReal Air 2 from 2023; even Google Glass, which came out in 2013 (!) had sufficient graphics for a HUD. What has changed is the availability of on-device machine learning that would allow for dynamic, interactive, contextual graphics. In fact, if it paired with a phone, you could even offload the heavy lifting for harder tasks and create an astounding experience. You’d just need to truly narrow down the use cases. By only doing very simple graphics and a limited number of tasks, you could plausibly get all-day battery life. And now that there are electrochromic glasses like the Ampere Dusk, you can use the glasses indoors and outside with the press of a button, so you can also take it everywhere. Apple has also built awesome directional audio into the Vision Pro, so you could imagine using that instead of requiring AirPods (though of course you could pair it for more privacy; another Apple Silicon home court advantage).

The way I see it, there are four killer features, and amazingly, they are all doable today:

Live navigation

Live translation

Object identification

Visual aids (like presenter notes)

Not only are they achievable, they’re easier than ever to do. They are also, frankly, applications that work just as well with an accessory to the phone rather than a replacement. The AirPods have proven that there is a $20 billion market for accessories that work well with the iPhone. And since no one wants to take pictures with their glasses, you not only have removed a battery draining feature, you’ve removed the social Glasshole stigma that accompanies products like the Meta Ray Bans. How can you be a jerk for recording people if that isn’t even a feature?

This is also a product Apple is uniquely positioned to make thanks to Apple Silicon: they could create an ultra-efficient chip with a machine learning core, an ultra-low latency communications chip for connecting to the iPhone, and offload the heavy tasks to the iPhone like it does with AirPods. It’s like the iPod: taking something super cutting edge and only using it for a few narrow but awesome applications.

Imagine you’re at a conference, and wearing your Air Vision glasses that paired with the iPhone and AirPods. You could initiate navigation from your phone or by voice with your Air Vision. Instantly, your glasses use an edge machine learning model that detects objects to help you navigate with contextual arrows that point the right way using Apple Maps. For indoors, they use the tech designed by Hyper. If someone talks, you can have the language translated instantly to your language but in their voice with AirPods while signs are translated by the Air Vision. On the way you see an unfamiliar but eye-catching skyscraper; the Air Vision recognizes that you’re staring and pulls up a 2 sentence description, letting you know that it’s a local landmark. Later, you present with Keynote. You don’t need to look down for your presenter’s notes. They’re right there on your face. At the end of the day, you go to a basketball game. Your Air Vision asks you if you want to display live graphics; you say yes, and while you’re in the stadium you get your own personal Jumbotron. When you leave to get snacks and go to the bathroom, it’s smart enough to change from a Jumbotron to a small score tracker so you don’t miss anything.

There is a version with regular glasses (with or without prescription) and a version with sunglasses. They each cost $500. They don’t work without your iPhone, but neither do your AirPods, and you love them. Of course, you buy both.

Mac Vision: The Anywhere Desktop

Let’s contrast this vision with the futuristic representations of immersive spatial computing. Ready Player One. Snowcrash. These are ultra immersive devices that entertain you. They make you perceive depth. Left unspoken is the idea of work. We need more and bigger screens, yet they take up more and more space, and then when we travel we have the same 15” screen we’ve always had. What if you could have infinite screens without needing a giant desk and you could take them anywhere?

Whats the solution? It’s the Mac Vision.

The Vision Pro is trying to cram in a HUD, but you can’t take it anywhere. The battery life isn’t good enough to use for extended use cases and it’s too heavy to wear comfortably for many hours. It’s too delicate for travel and is missing a lot of key features. Somehow, they shipped a work machine with a cruddy keyboard and no hot-swappable battery. The reason is that they didn’t realize the Vision Pro isn’t the successor to the iPhone; it’s the successor to the Mac. What it offers is the unification of the desktop and laptop experience. That’s never before been possible before but it would be amazing. And like the iPhone, you’re getting a bundle of devices: the most capable Mac ever and a breakthrough portable screen that gives you as many as you want.

With that in mind, they can ditch the expensive Eyesight. That will cut weight and cost dramatically while making it more durable (and therefore travel-friendly). Ship it with an M3 processor so it can truly replace a MacBook (it should have never been a generation behind; if anything, it should be the first product to get a new M Series to drive sales). Introduce a special communication protocol between Mac Visions. Produce a special, portable Mac Vision keyboard and make a sleeve on the case that can hold the Vision Keyboard. Don’t worry about recruiting game developers; games take forever to make. Just get enterprise app support. That’s easier anyways and can mostly be handled with Mac app support and a good browser. And for entertainment, a few key sports partnerships is enough. Make the battery bigger so it lasts 6 hours, especially now that you don’t have to power the Eyesight, which probably uses a lot of power. Since people will work all day, make the design ergonomic even when plugged in. Don’t use heavy aluminum; use a thin aluminum coating over plastic to cut the weight (and cost). And push the Vision video chat “persona” available by SDK to everyone from Day One: Zoom already supports it, but everyone else like Microsoft Teams should too to normalize the concept and maximize business user appeal. Build some truly immersive built-in apps—what if you place yourself in Apple Maps street view and travel anywhere in the world for free?

Imagine you’re on the train to the office. You pull out your Mac Vision. You open Slack in one window, Word in another, and Salesforce in a third. You get an iMessage from your daughter, which you answer. It’s amazing; you have almost no space yet you have 3 concurrent monitors open. With pass through, you’re fully aware of what’s happening around you and don’t miss your stop. You put your Mac Vision in its slim hard case and go. It’s smaller and lighter than your MacBook ever was. At work you pick up and resume. You couldn’t get budget for a second screen before. Now you have as many as you want. When it’s time for lunch, you plug in your battery pack and walk off. On the way home, you pull up Apple TV+ and watch an immersive show you love streaming, like Silo, with spatial audio synced to your AirPods Max. The episode finishes just in time. You’re plugged in on the train so you don’t run out of battery. Once you’re home, you’ve gotten 10 hours of use, work and entertainment.

It costs $3000. But your MacBook Pro was $2500 with the same processor and just a 15” screen. The battery life is lower, but you never used your MacBook for more than 5 hours without plugging it in anyways. You happily replace it with a Mac Vision.

And as the technology improves, the problems will start to get better. The Mac Vision will get smaller with better battery life. The Air Vision will be able to display more advanced graphics. And one day, these products will likely converge into one.

Defining the Vision use cases by breaking them up also short-circuits one of the shocks for the Vision Pro: the sticker price. Apple didn’t define its market so the press did it for them, and they chose Oculus devices, which are 5x cheaper. Splitting the Vision Pro into the Air Vision and Mac Vision would eliminate any comparisons to such comparisons because both feed into different markets. The Air Vision would be viewed as a pairing with the AirPods Pro, which cost $250. Sure, $500 Air Vision glasses are more expensive, but not exorbitantly so, and in fact that is the same price as the AirPods Max for a sci-fi product. You’d be delighted to spend $500 for that product, even to spend $1000 for regular glasses and sunglasses. Similarly, the Vision Pro doesn’t seem so expensive when you compare it to the cost of a Mac Studio with two high-end monitors, which could easily cost over $5000. But with Mac Vision, the comparison is explicit. It’s a MacBook replacement. And considering that MacBooks now regularly exceed $2000-3000, you’d feel like you were getting a bargain for a Mac Vision. A computer with infinite screens, and you can take it anywhere, and it’s just the price of a low-end MacBook Pro? Sold.

Despite that, you’d end up with a better price position while actually getting customers to spend more. I think most people would have bought both an Air Vision and Mac Vision. In the end, the customer would have still spent $3500 but spread across 2 devices. Each would purpose built and feel like premium value. Customers wouldn’t even notice.

Choices make products

Making choices was the only requirement for these exercises. These products are both possible to build today. The Mac Vision is just the Vision Pro with unnecessary feature bloat cut away. And the Air Vision is just the Apple version of smart glasses that already exist. Apple is uniquely positioned to offer these products. They make the world’s best chips and can integrate their products to buttress each other.

This future is possible today. I hope Apple gives it to us.

But more importantly, the essence choice is to allow you to build the future by pulling forward only the most crucial features at first. The most cutting edge technology is already out there. It just isn’t fully developed. Thinking about what that technology is good and bad for allows you to map that onto the problem space you are working on. As long as the technology is rapidly improving, you can add the missing use cases later and even anticipate them. You’ll always seem ahead of the curve.

What works for products can also work for venture. In a 2010 talk at Stanford Business School, the founder of Sequoia, Don Valentine, explained the simple reason that Sequoia seemed to have seen the future. He had been the head of sales for National Semiconductor, and he was a believer in Moore’s Law, so he had spent five years mapping out the next several decades of the computer industry. He knew what people would want and what the gaps were. Mapping that out and comparing it to the state of the art then became a marketing exercise.

What you cannot do is give up on thinking. The reason you might want to avoid making a choice is to avoid risk and avoid the difficulty of thinking things through. But as in many things, not doing the hard part and running away from risk is often the riskiest thing of all.