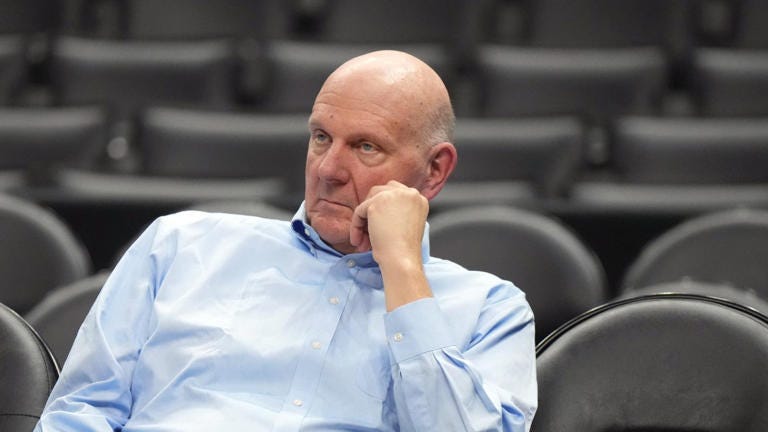

Is Steve Ballmer the Most Underrated CEO of the 21st Century?

A reconsideration of the Microsoft CEO everybody loves to hate

In light of the recent, amazing drop of the Acquired Podcast’s Microsoft: Volume II, which covers the Ballmer era, I decided to drop an essay from the vault. Here, I write about someone who many consider the worst CEO of the modern era. But is that right?

When looking at CEOs of the recent past, Steve Ballmer is usually painted in a terrible light. Forbes once called Ballmer the worst CEO in America. Shareholders like David Einhorn called for him to step down. Vanity Fair called his entire term as CEO a “lost decade.” The story goes that he was such a bad CEO that he was paid $1 billion just to quit. His ultra-high energy persona became such a joke that one of the most flattering profiles of his tenure was called “No more Mr. Monkey Boy,” referring to his infamous dance. Microsoft’s stock performance fell during his decade at the helm.

That said, much of the analysis of Ballmer’s time as CEO has been histrionic. We now have the benefit of time, so we can evaluate how he did with more rational eyes, as well as the benefit of hindsight.

So, here is a deep-dive review of Steve Ballmer’s performance—the good, the bad, and the ugly.

Although it would be incorrect to call Ballmer the best CEO of the 21st century, he may be the most underrated.

Ballmer was good at normal business stuff…

The main Microsoft business did well under Ballmer. He brought revenue from $15 billion to $70 billion during his tenure and earned nearly a quarter trillion dollars of profit while CEO, perhaps unsurprising for a sales-focused leader. He launched several successful and market-leading products, including Xbox, and acquired important strategic ones, like Skype. If the job of a company is to make money and the job of a CEO is to steer the company’s financial performance, then Ballmer succeeded at its most important mission.

Ballmer’s most impressive choice is succession. Most CEOs fail here: according to a Harvard Business Review article, over 40% of public company successors fall behind within 18 months; more still fail to excel at all. Satya Nadella, now the CEO of Microsoft, was merely one of several candidates considered, and he was the dark horse option. Like any blue chip company, they also attracted several outstanding outside candidates like Alan Mulaney, who turned around Ford, and Pat Gelsinger, now CEO of Intel, and among insiders Tony Bates was considered the most likely option. But Ballmer made the smart move: he elevated a technically capable leader who was leading cloud, which was, at the time, Microsoft’s fastest growing sector. Satya will likely go down as one of the best successor CEOs ever. Though Satya’s success is all his own, choosing him as a successor deserves a lot of praise. And getting something big right that most people get wrong makes it especially so.

Arguably, Ballmer did a good job with developing people overall, not just Satya. Cultivating developers was Ballmer’s big thing. It always has been. And it is actually really difficult to do—Apple, Google, Amazon, and pretty much all of Microsoft’s peers have been way less successful, if not outright failures in some cases. Ballmer also created the One Microsoft initiative, creating a more cohesive organization. It was panned at the time by commentators including Ben Thompson. But it worked, and today remains the bedrock of Nadella’s Microsoft.

Notably, this was all done while operating with the difficult aftermath of antitrust. Bill Gates, who remained on the board, famously said that not settling the antitrust case early was his “biggest mistake.” Well, he didn’t have to live with the consequences of that mistake—Ballmer did! And that mistake meant that every new decision was under government scrutiny. Achieving any growth under these circumstances is impressive. In fact, he just generally seems like a reasonably competent manager. Since he bought the Clippers, for example, they have nearly doubled in value and half of their conference finishes ever have occurred under his short tenure. They’re even doing better than the Lakers!

Despite this, Ballmer was never rewarded in the stock market. Microsoft stock fell approximately 40% during the Ballmer Era. He can’t blame this on the Dotcom Bust either—the NASDAQ only fell 10% during that time. To add insult to injury, IBM even briefly exceeded Microsoft in market cap in 2011.

There’s a reason for that.

…but Ballmer was not a product visionary

Steve Blank once observed that visionary CEOs rarely have visionary successors because they choose operators as successors, and operating and vision are usually mutually exclusive. Ballmer, as mentioned above, was a truly excellent operator—increasing revenue 560% in 12 years is impressive anywhere and is particularly so at Microsoft’s scale. But in several key areas, Microsoft failed to lead because of product failures.

The emblematic failure of the Ballmer era is the iPhone. He missed this, and there’s no way around it. For everything Ballmer did right, this is legitimately one of the biggest modern business failures.

Most damningly, even 15 years later, he still tries to rewrite history. Ballmer has come up with lots of excuses over the years, none of which hold up even a little. It is possible that he still doesn’t understand why Microsoft lost to the iPhone, which would be even worse.

Ballmer originally used to say that his doubts stemmed from the iPhone’s price, and that carrier subsidies were a “business model innovation.” The problem is that this is just incorrect. Phone subsidies were common, including for Blackberry and the Razr. Ballmer has also said that Microsoft was too late to the mobile phone market. This is also wrong—Microsoft had Windows Mobile, and in 2006 it was the most popular OS with 37% of the mobile phone market.

Antitrust has also come up as an excuse, but that whole episode concluded half a decade before the iPhone launch. Years after Ballmer stepped down he was still obsessing over Microsoft’s dearth of hardware products, yet Google’s Android, which is more widespread than iOS, has never had a successful first-party phone.

The reality is that Ballmer was just wrong about what people wanted. The iPhone’s critics saw it as an overpriced, underpowered machine using an overcomplicated OS based on desktop-class software. Ballmer was one of those people. At the time, he thought the iPhone needed a keyboard to succeed and said so contemporaneously during his famous news conference following the unveiling. Buying Nokia was the perfect proof he didn’t get it. A total waste of money in chasing where the ball was, not where it was going.

The other huge product failure for Ballmer was the OS. Ballmer continued to focus on Windows as the lynchpin of Microsoft’s strategy because that was what had always been its forte. While OSes remain strategically important, they are not commercially important. Despite that, while Apple kept decreasing the cost of OS X until it became free in 2013, Ballmer kept trying to get people to pay more for Windows. When Ballmer stepped down, Windows had already begun a rapid decline in global OS share. Android surpassed it in 2017, in large part due to being open source.

This was very much accelerated by the failure of Windows Vista, the biggest desktop release under Ballmer’s tenure. Vista was buggy, it had security flaws, it was slow, and it reduced battery life, which was particularly bad during a time when consumers were buying more laptops and needed more efficient processors. Developers, long Microsoft’s biggest constituency, hated building for it. The criticism was so intense and universal that Windows Vista criticism has its own Wikipedia page. It is one thing to fail so badly that you precipitate a massive loss of market share in a previously-successful product; it is another to do so in a product that you yourself consider important.

As a general matter, this is where Ballmer most critically failed: he was not a product leader at a time when Microsoft needed great change. Ultimately, this is why he couldn’t stay as CEO.

However, Ballmer’s choices set Microsoft up for success, legitimately…

Though Ballmer was a terrible product mind, his business choices set Microsoft up for success. You could even argue that Microsoft still stands on Ballmer’s shoulders.

The most important example of this is Azure. Nadella is, rightfully, praised as the visionary and driving force behind Azure. That said, Azure started under Ballmer. In fact, it began with a Ballmer acquisition, Groove Networks. And as CEO, Ballmer could have killed Azure at any time. In fact, most CEOs would have. The pressure to do so must have been intense because it meant going against every instinct that Microsoft had built up to make it into the most valuable company in the world: selling ultra-high margin software while avoiding cannibalization and hardware. Not only that, but Azure initially stumbled because it was offered under a Platform as a Service model, not Infrastructure as a Service. How many CEOs would have had the vision and courage to stick through with it, especially under criticism from a board that already wanted him gone? Nadella himself praised Ballmer for supporting Azure in its early days. He deserves immense credit for this.

Ballmer also pushed for new products that led to Microsoft having the most diversified revenue of any large tech company. Bing, for example, was a success. Though Microsoft didn’t unseat Google, Bing is now extremely profitable, with revenue exceeding $8 billion, over half of Windows’ $15 billion—in fact, if you include LinkedIn’s $10 billion in revenue, Microsoft now makes more in advertising than it does from Windows! Ballmer also personally kept Microsoft Research funded despite high shareholder pressure to stop. His investments in Office and Azure allowed for the launch of Office 365. Today, Microsoft Research’s innovations have powered many of their most popular and futuristic projects. And the distribution machine Ballmer built is what has allowed Azure to have a real shot at unseating AWS instead of GCP.

Those investments positioned Microsoft to be the only credible company that could back and save OpenAI. It is the apotheosis of investments from the Ballmer era that bore fruit a decade later: it would not have happened without the cloud compute of Azure, without the distribution of enterprise sales, without the data crawled by Bing, without the staff at Microsoft research, without the GPU relationship with Nvidia that started with Xbox, and more.

Putting this all together, we can see how Ballmer set up Nadella for success. It has set Microsoft at the forefront of the AI revolution as the first- or second-most valuable company in the world, depending on the day.

…though Ballmer held on to the past too long

Ballmer has described himself as loyal. It’s therefore fitting that some of his biggest mistakes involved holding on too long. Primarily, everything Ballmer did was about supporting Windows instead of evolving Microsoft. There were times where holding on was a good thing, like with Office, where fighting hard to maintain Microsoft’s leadership gave it a powerful flagship product to power through the cloud era and push its ecosystem with Teams and more. But there were other times where it hurt Microsoft greatly. After all, Ballmer’s obsession with the 90s-era Windows-centric strategy also meant that he did not see the threat of AWS quickly enough, giving them a seven-year head start over Azure which Jeff Bezos called a “miracle.

Microsoft had a defensiveness in its culture stemming from the beginning from its need to convince people that software was even worth paying for, going back to Bill Gates’s famous letter to the Homebrew Club. It is therefore no surprise that Ballmer called open source a “cancer.” In fact, Satya’s embrace of open source is probably his biggest break from Ballmer. Though closed source worked for the 90s, by the 2010s the future was open source. We don’t know how Ballmer would have adapted because this was after his time, and later in 2016 he was singing open source’s praises. But had Microsoft continued down Ballmer’s path it would have been doomed to a slow, irretrievable death given how important open source became to enterprise software. Although it is possible to imagine Ballmer buying Github, it is impossible to imagine him open sourcing VS Code.

Ballmer’s “bull dog” personality also caused him to hold on to outdated management practices for too long. Gates was notoriously difficult to work for and created a competitive culture at Microsoft. Ballmer was no different, and he was most famously a proponent of the “stack ranking” system where the bottom 10% of all engineers were fired every year. This lead to a culture of fear and an average turnover rate of 8%. Unsurprisingly, when Ballmer stepped down, it was the first thing to go. He kept this system despite implementing One Microsoft, meaning that Ballmer’s management style record must be viewed as flawed.

So why the Ballmer hate?

Some of the hate comes from Ballmer’s personality. Ballmer’s flamboyant personality makes him an easy target, but he’s a smart guy who majored in applied mathematics at Harvard and outscored Bill Gates on the Putnam exam. His intense persona is part-real, part-act to motivate employees, and besides, his over-the-top performances were objectively less silly than those of Jack Ma. Ballmer overcame intense childhood shyness; his yelling was probably overcompensation and, seen in that light, actually admirable and endearing.

Yet more hate comes from the fact that Ballmer was a business CEO sandwiched in between two technical CEOs in an era where people are skeptical of nontechnical leaders, at least in the tech community. Ballmer’s predecessor is a genius programmer who was the richest man in the world for over two decades; his successor is an inspiring engineer whose technical vision is somewhat of a rewrite of Microsoft’s modus operandi. It is hard to not look bad.

But more than anything else, it is product. Microsoft was seen as incredibly scary and dominant and it just completely whiffed it in the most visible and embarrassing way possible. Even Paul Graham once said that Microsoft was dead. Microsoft’s mobile position is completely unrecognizable relative to its position in all other computing verticals, it didn’t win the #1 spot in cloud computing that it should have had, and it almost missed open source. Even if Ballmer did everything else right, such big product misses would exclude him from ever being considered a truly great CEO.

But being the best isn’t the same as being underrated. Most people act like Ballmer got a report card of straight F-minuses. But in truth, as a student of business, he received a mix of A+s, Fs, and normal Bs and Cs. A pupil with extreme talents who had clear weaknesses and wipe outs. A 3.3 or 3.4 GPA hiding extreme strengths and weaknesses. Interesting, and not worthy of only being judged by his best, but far better than judging him solely at his worst like most people do now.

So was Ballmer the worst CEO ever? Clearly not. He was the personification of a dribble drive motion: he might have taken some hits, and he might not have been the star, but he set Microsoft up for layup after layup.