Epicycles of thought

Avoiding overcomplicated mental models

For thousands of years, people believed the universe revolved around the Earth, not the Sun. The grade-school story is that Galileo developed an amazing telescope, discovered this couldn’t possibly be true, and proved the heliocentric model. There is a problem with this tale, however. Other scientists before Galileo had developed better telescopes too and found problems with geocentrism, yet it persisted; better optics can’t be the entire explanation. What saved geocentrism for centuries was the invention of epicycles.

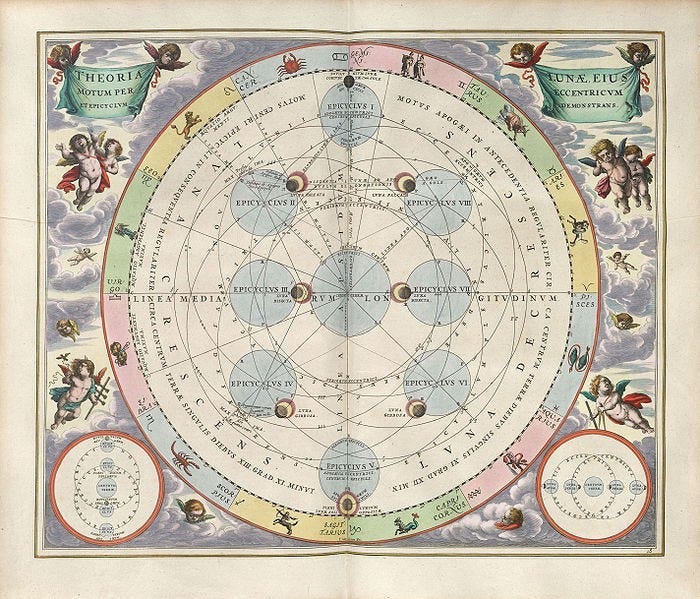

What are epicycles? If you imagine an object orbiting another, you will of course model that as an ellipse. The problem is that if you think the planets are orbiting the Earth and they are actually orbiting another object, say the Sun, over time you will have observations that fail to fit that model. Rather than treat these deviations as disconfirming evidence of geocentrism, blinded by religious dogma, astronomers added mathematical complications to their models of planetary orbits starting with Apollonius in the 3rd Century BCE. These modifications were called epicycles, and they were very convenient for the committed geocentrist — when the model broke down, an astronomer would just add a new epicycle and create an even more convoluted view of the heavens that could last for a little longer.

The importance of epicycles is not the (interesting) history of science but the fact that they describe a common intellectual pattern. We engage in epicycles all the time to preserve something that we want to believe is true, regardless of whether it actually is. Armed with the fig leaf of trying to figure out a complicated reality, we hold on to theories of the world like ideological investments, afraid that by moving on we will devalue the intellectual capital we have expended. So we just add epicycles.

You should not avoid complexity, just unnecessary complexity. Albert Einstein said it best: your theory should be as simple as possible, but no simpler. In other words, your theory must incorporate everything that is true and that has explanatory power; if it reflects a reality that is in fact complex, then so be it. If you discover a new wrinkle, incorporate it. But if your theory keeps failing and the only way to make it fit is to add complexity, eventually that is a sign the core underpinnings are wrong.

The key sign that you’re engaging in epicycles if your theories never get simpler at all, and if threats to your core beliefs are always met not with skepticism but with hostility. The complexity of reality means that your mental model will get naturally more complex as you go out into the field. But if you are learning you will also be falsifying. Some beliefs will get thrown away. Some mysteries will remain open. If that never happens and you just keep adding more nuances just to keep up with preserving your core theory, to feel like everything has a tractable solution, those aren’t details — they’re epicycles. Epicycles turn falsifying evidence into confirmatory evidence by contorting the model to fit the data, creating a truth available only to the priesthood that understands an ever-more complicated view of the world. The hard part of rejecting all of this “evidence” is that you need to be able to see the theory fail to make sense and constantly reject new evidence without the theory itself being updated. To transcend epicycles requires you to actually think.

The greatest ally of epicycles is dogma. Geocentrism lasted so long because priests and philosophers decided that the Earth’s placement in time and space had implications for its spiritual importance. That made accepting heliocentrism anathema on a deeper level than science, which is the reason so many smart people toiled to preserve something whose falsity was increasingly obvious for centuries. The dogma was so strong that literally generations of technological improvement, which consistently produced falsifying data, was met with rationalization instead of rationality. That dogma is enhanced by authority figures, giants who made real progress but with a fatal flaw whose work we rightfully revere frequently at the cost of proper, fair critique. Our heroes only become dangerous when they become shields against thinking because, we assume, they have all the answers; the line between reverence and subservience is often exegesis. We can ignore the truth indefinitely if we want to, and our tool of choice is epicycles.

As proof, epicycles lasted, extraordinarily, for over a millennium. Accepting them often is a means to avoid an uncomfortable truth. Rejecting heliocentrism didn’t just mean rejecting a scientific model. Rather, it meant rejecting a philosophical view of our place in the world held by Aristotle and the Catholic Church alike; it meant disproving epochal knowledge passed down from ancient foundational figures like Ptolemy. Escaping epicycles requires not just openness and honesty but oftentimes bravery and fortitude to stand against conventional wisdom. Epicyclic models often get adopted by whole communities, so rejecting them often means standing alone and accepting isolation.

It is lonely to reject epicycles. The more there are, the more entrenched. But the reward is operating under the correct model and being the only one to go in the right direction.