The Question on Artificial Ice and Progress

A model of a failed scare campaign begs the question: why does it work now?

In the modern era, newspapers published countless, breathless stories about Tesla car fires even years after the data showed that EVs had lower fire risks than ICE cars. Now we see the same with Waymo cars even though the early insurance data across 3.8 million miles shows that AVs are already safer than humans by outrageous margins—a 76% reduction in property claims and 100% (not a typo) elimination of bodily injury claims. Bogus astroturf campaigns pretend that they are fighting over “local control” of AVs when they really just want to tax them or ban them.

These days, it seems like new technologies face an unprecedented onslaught. Political opponents, astroturfing, histrionic media stories, and more. It can make you feel like these people are stopping progress. We see it for many new technologies, like nuclear power, supersonic flight, and autonomous vehicles, all slowed down by regulation caused by fear mongering. We think that if only we could make people see the light things would move faster.

Then I learned about artificial ice.

For most of history, ice was harvested in the winter and stored throughout the year. Amazingly, we got the Model T before we stopped using natural ice.

And it turned out that artificial ice faced its own resistance. There are some interesting lessons in there in how progress happens, but it leaves a brooding mystery for us to solve to unlock progress in our own era.

The Importance of Ice

Since ancient times, humans have used ice to store and preserve food. There are Bronze Age Akkadian records of ice houses that would store ice collected during the winter for summer drinks and ancient Egyptian clay pots from 500 BC that are believed to have stored ice. Yet without the ability to create artificial cooling, the only way to get ice was to harvest it, which of course made it very expensive. Whether Aztec, Akkadian, or Austrian, ice was used largely by the rich. If the winter was not cold enough, an entire region could face an “ice famine.”

However, the rise of American population centers in relatively hot climates created enough demand to foster a robust ice trade starting in the early 19th century, pioneered by “Ice King” Frederick Tudor, peaking at nearly $500 million.1 Chilled drinks, once the province of kings, spread to the masses. Previously-infeasible foods like ice cream became widely accessible. It became possible to transport produce in such quantities that special rail cars were developed. Medicine cold chains were literally life saving.

But of course, when society becomes so dependent on ice, depending on natural cycles becomes less tolerable. Enter artificial ice.

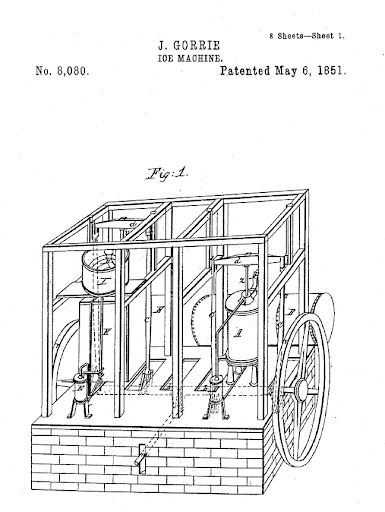

Technologically, artificial ice is an invention centuries in the making that solved this serious societal problem. There have been many iterations of technologies, from a Spanish physician who used salt to lower water temperatures to more modern compression refrigerant systems. The key breakthrough was the discovery of the vapor-compression cycle by William Cullen, which is how refrigeration still works today. Decades later, John Gorrie realized this could be used to make ice. Various improved systems were proposed, varying in which refrigerants they used, the design of the components of the system, and so on. The first practical implementation was built in Australia, where it was a commercial success due to the impracticality of shipping ice great distances from Britain. Although artificial ice was initially very expensive, costs came down over several decades,2 eventually resulting in the cessation of ice harvesting. Most people today wouldn’t even realize that for most of human history ice was only found in nature.

But along the way, artificial ice faced a punishing scare campaign. What is so notable is how similar to what we see in the modern day.

Scandal and Slander

Several states have decided to ban artificial meat. Those who wish to do so scare and recruit sympathetic farmers to talk about how how lab-grown meat is “unnatural” and scare consumers into thinking that meat is unclean, all in support of legislation banning such products. That kind of coordinated campaign is exactly what happened with artificial ice.

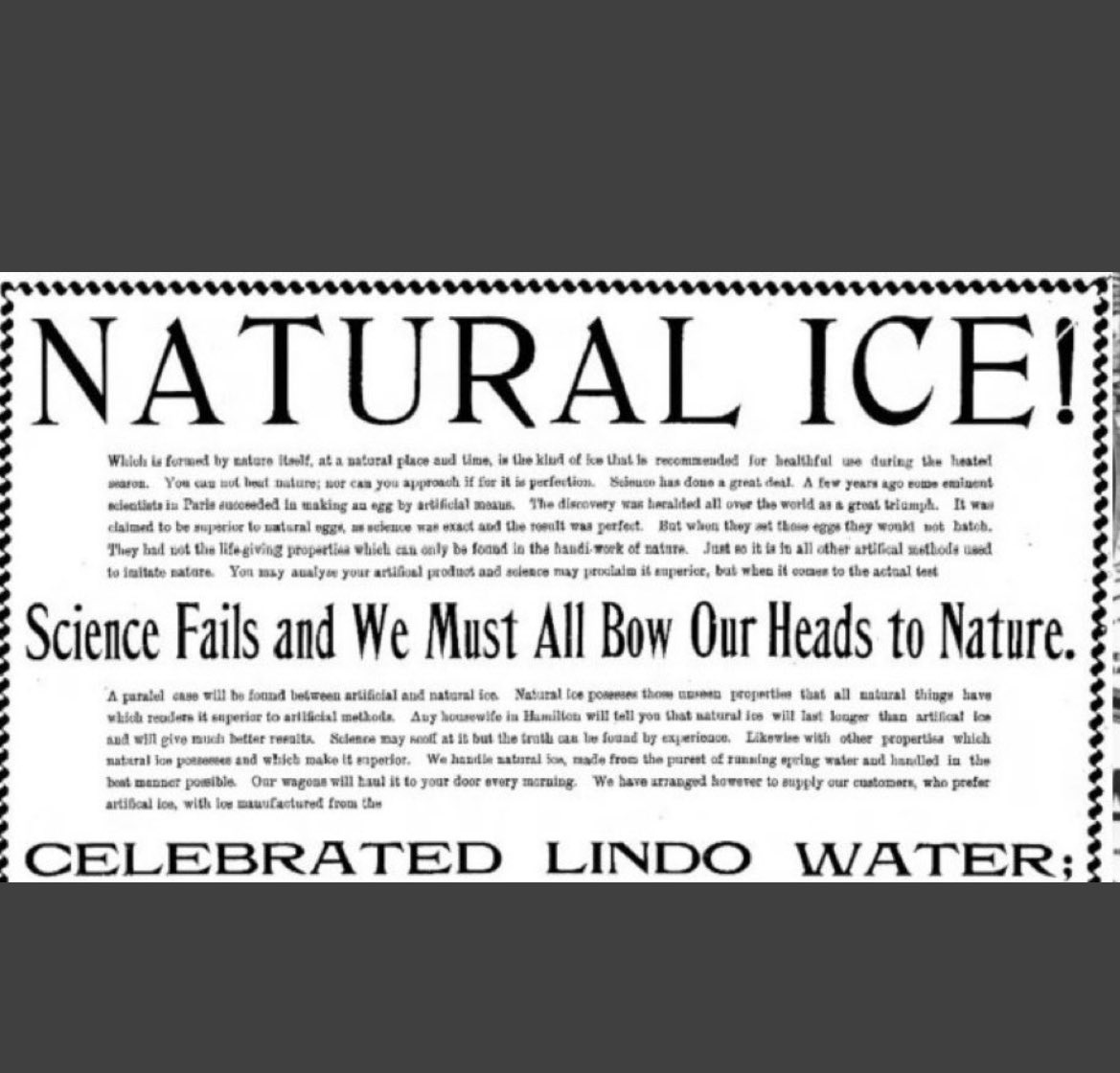

In his book How We Got to Now, Steven Johnson explains how the ice industry—which coined the term “artificial ice”—spread rumors about the new invention, even claiming it could carry disease. It didn’t help that the Ferdinand Carree ammonia refrigerators were the ones that first took off. Ammonia-produced ice would leave a white residue when it melted. Ice plants could explode or have ammonia leaks, leading to calls for regulation. Natural ice manufacturers ran vicious ads, like this one from Lindon Ice that says “Science Fails And We Must All Bow Our Heads To Nature.”

The newspapers were part of the effort to keep natural ice alive. After all, an 1880 New Orleans newspaper article noted that there remained a “natural prejudice” in favor of natural ice. Even in 1911, nearly 50 years after artificial ice appeared, a newspaper in Scranton praised the virtues of artificial ice. A Philadelphia newspaper published an elegy about a sympathetic family’s ice harvesting business. Fears were spread about the fitness of artificial ice for human consumption, as memorialized in an 1889 academic article from the Texas Medical Journal; never mind that natural ice had greater health concerns, like water runoff pollution and typhoid.

The assault in the press was so severe that Gorrie could not attract investment and died penniless, perhaps delaying progress in refrigeration by decades.

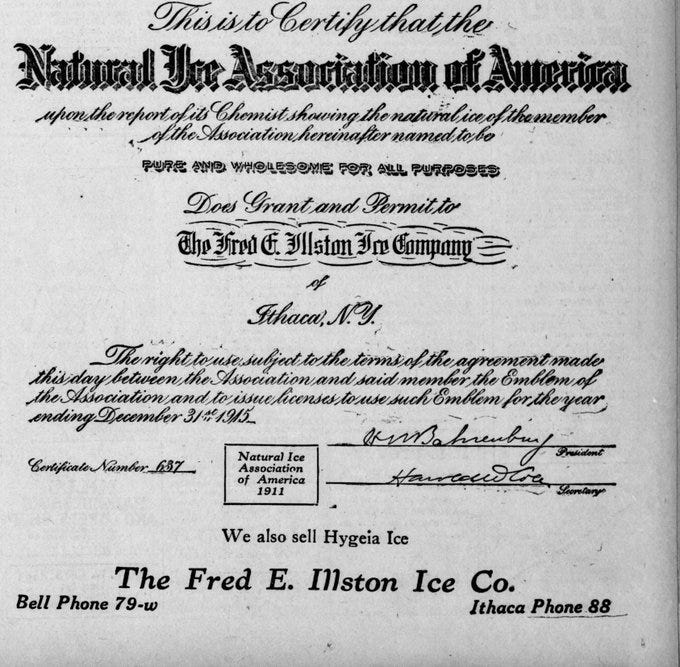

The natural ice industry coordinated this decades-long campaign alongside corrupt politicians. Charles Morse formed a monopoly called American Ice Trust with the support of New York City’s first mayor, Robert A. Van Wyck, increasing prices in the Ice Trust Scandal that helped lead to the downfall of Tammany Hall.

They formed the Natural Ice Association of America, which was a combination of what today we would call a PAC and an astroturf operation. According to the Natural Ice Association’s first meeting minutes, it was primarily focused on creating a false debate around cleanliness. For example, it hired W. T. Sedgwick, a professor at MIT, to produce poppycock like the claim that water tends to purify itself in freezing, and H.W. Mill, the director of epidemiology for the Minnesota State Board of Health, to argue that the apparent association between natural ice and typhoid was likely caused by other contaminants, like dirty hands. This is not unlike various energy groups that fund anti-green energy groups and get politicians to say their stuff is “good for humanity,” or anti-tech groups that scare people into vastly exaggerated concerns about the water usage of data centers.

All We Can Learn is a Question

But here’s the interesting thing: the scare tactics didn’t work.

Society had come to depend more on ice as it urbanized and industrialized. From 1880 to 1914, American ice consumption tripled. That made ice famines less tolerable. An 1898 British ice famine, for example, was so severe that it led for a national call to develop ice plants.3 Thanks to exposure, public opinion turned increasingly positive towards this always-exciting technology. In 1914, artificial ice finally overtook natural ice. More ice was produced than harvested. Society never looked back.

Zooming out, this pattern is not unique to artificial ice. Looking back, in fact, it seems like most technologies have faced these types of headwinds. No less than Frederick Douglass helped lead campaigns against vaccines. Thomas Edison used to scare people away from AC currents by using them to electrocute animals and newspapers published cartoons about the horrors of technologies like electricity. Even the Luddites weren’t unique; the word “sabotage” comes from French Luddites who threw sabot shoes into industrial machines. Decelerationists, in other words, will always be with us.

Despite all the fear-mongering, we produce goods in factories, we vaccinate our kids, we don’t use DC for all our electricity needs, and yes, we drink Coca-Cola with artificial ice.

What is clear from the history of technology is that everything that impedes progress now—astroturf fear mongering, political corruption, legacy media nostalgic sob-stories, hobbling anti-progress regulation—attempted to impede progress in the past too. These tactics were used because they appeal to timeless fears and weaknesses in human society and, perhaps, even the nature of our souls. These techniques are therefore timeless and we should not be surprised at all that they are emerging today in response to new technologies.

What is remarkable is that these various scare campaigns, all of which corresponded to calls for boycotts and bans, failed. Today, however, activists use the same tactics to great success, resulting in legislation against lab-grown meat, nuclear power, and much more. The question is therefore not how to stop spasms of technophobia but why the same attacks are more successful now than they were a century ago.

The answer does not seem to be that we are too far from industrialization; these techniques did not seem to work that well until recently. Children watched cartoons as recently as the 1950s like “A is for Atom” extolling the marvels of nuclear physics, even after the despairs of the “industrial wars” we now know as the World Wars. It is impossible to imagine that today, but it was not so long ago a woman could remark on how “wonderful how DuPont is improving on nature” with their chemicals at the 1936 World’s Fair. “What happened in 1971?”, indeed.

It seems like fear campaigns failed for the simple reason that society had a different attitude towards progress. But that does not answer why they felt that way.

Perhaps it has to do with the immediacy of the fears of the past. A century ago, people were worried about whether they would get sick from typhoid and die. Today we worry much more about long-term effects that are uncertain and require decades to measure. As Virginia Postrel put it, “To our 19th-century ancestors ‘nature’ was a source of peril rather than purity.” The problem is that positive attitudes towards technologies continued far past the point of subsistence industrialization.

Today’s fear campaigns are different. They are more amorphous. The result is a strange situation where only a rare injectable meme actually stops progress of the thing itself (say, nuclear power), but they do almost all contribute to a general environment that conspires to limit progress in general.

When Teslas were new, there were stories about electric cars catching fire even though they are 11 times less likely to catch fire than a gas car. On the one hand, electric vehicles live on. On the other hand, people still live with this fear, and it has slowed adoption in the United States. This is not the only example. No matter how many times vaccine myths are debunked, there is a subset that stubbornly refuses to get vaccinated because they have sincerely come to believe that Bill Gates wants to give their kids autism and turn them into 5G towers. Notably, even though the original Wakefield MMR-autism article has been disproven, many people still believe that claim and have even gone on to other unrelated vaccine related fears, like dosing schedules. Even for technologies where exposure decreases fear, like autonomous vehicles, attempts to ban them continue. The deep question is how to make people into what Peter Thiel calls definite optimists.

Perhaps we have simply adopted another value system. Way back when, people made much more direct trade-offs: am I better off, regardless of whether the cause is natural or invented? Today, we seem to value purity and assume that natural is better. This could be true, but it would still be circular. We would still not know why we came to adopt this new value system at the expense of the progress that got us there.

The original article calling for progress studies by Patrick Collison and Tyler Cowen called for a better understanding of the causes of progress. While it is true that we do not know why the Industrial Revolution happened when it did, the episode over artificial ice suggests, as Joel Mokyr argued in his now-Nobel Prize winning book A Culture of Growth, that the key factor is the attitude of people. Perhaps the most important question for progress studies is not one of studying institutions and the network structure of universities but rather solving the social psychology of fear of the future. What this vignette suggests is that the reason progress has stopped is not some arcana surrounding science funding but the simple answer that we wanted it to stop. And that is a most frightening prospect.

As of now, there is no satisfactory an answer to the question: why are we so much more fearful that anti-progress propaganda can work and so much more resistant to good news? Answer that and you might unlock a whole lot of progress.

$500 million in 2010 dollars. This was helped in significant part by large investments made by Tudor in ice harvesting and transportation technology, as well as advances in the railroads.

For a long time, one of the main issues limiting the spread of artificial ice was cost. In 1899, artificial ice cost $2.13 per ton, which was the same as the price of natural ice in 1847. While artificial ice was expensive, it found its initial success in circumstances where ice was highly limited, like the South during the Civil War, and industries that required lots of refrigeration, like beer breweries. That allowed it to invest in efficiencies and work its way down the Wright curve. But as we will see, there were other issues that kept people away.

This is a persistent story in technology adoption: the technology is already there, but it takes a crisis to make everyone adopt it. With elevators, for example, it took an operator strike in the early 1950s, decades after New York City became dependent on skyscrapers, to cause mass adoption of automatic elevators even though they had been ready for decades.